I want to consider two works on mushrooms in this final blog post, and think through how they might help us burgeoning mycelium appreciators and as subjects under a capitalist political economic regime.

Anna Tsing, in her book The Mushroom at the End of the World, looks at the relationships that mushroom pickers, buyers, supply chain capitalists, and consumers have with the Matsutake, also known as the Pine Mushroom (Tricholoma matsutake or Armillaria ponderosa). Tsing argues that by analyzing such as small commodity, the mushroom, we can reveal and understand the vast arrays of histories and politics that are a part of its collection and consumption. Through these analyses, Tsing argues, we can look at the ways that the commodity structures impact broader political acts globally and find ways to disrupt or use the structures to create viable networks of care and aid for living in the wreckage of climate collapse.

Tsing’s work is fascinating for a number of reasons. I think foremost she has done excellent work exploring the political economy of the matsutake market. The mushroom, growing best in forests that have been heavily disturbed by human action such as logging, are highly prized in Japanese haute cuisine, but are becoming more and more difficult to find in Japan. Matsutake mushrooms, with their distinct peppery and spicy smell and taste can fetch upwards of 800$ per kilogram in Japan. Good specimens will run 80$ per mushroom. Despite the high cost of the commodity, workers engaged in picking are often in the most precarious positions. They operate as independent hunters, forced to compete with other hunters and sell their finds to bulk buyers who run near monopoly wholesale operations and hunters tend to be from populations that are already systemically disempowered (Tsing discusses how pickers are often migrant labourers, veterans without health support, etc…).

Throughout her discussion, Tsing notes that noticing the connections that the Matsutake mushroom harvest makes between labour and capital, and between high class consumers in Japan and forest destruction in Korea or the west coast of North America, allows us to find novel forms of networked solidarity and community in a world collapsing under the weight of capitalist accumulation and its consequences. Troublingly though, Tsing underplays the visceral reality of people living through the collapse and the reasons why they find mushroom picking as their only option. She portrays the matsutake as a symbol of hope, of finding ways to survive through the destruction. Her portrait of the mushroom however, is nothing more than a palliative for privileged persons who are too timid to stand up against the forces that are targeting people deemed superfluous. Mushrooms that live through destroyed forests can certainly be a sign of hope, but intentional or not, Tsing implicitly encourages a kind of blissful resignation to destruction.

Tsing’s patronizing distance from the lived realities of the precarious workers she portrays as ‘free’ in the woods picking mushrooms (as if living off starvation wages because nothing else is available to you or because the society you live in has thrown you aside is ‘freedom’) is not helpful to us if we want to organize to actually emancipate ourselves from imposed social conditions under capitalism. However, her analysis of the networks that are arranged to accumulate wealth with the matsutake is. Read alongside Paul Stamet’s work Mycelium Running, we can start to think through mushrooms not only as analytic devices that reveal capitalist relations in our networked world, but as tools for disrupting those relations.

Stamets, a mycologist from Oregon, writes of his experiments that show the ways in which mycorrhizal fungi (mushrooms that are symbiotic with other plants) have demonstrated the capacity to filter water, or even breakdown toxic and radioactive materials through a process of myco-remediation. Beyond these capabilities, limited though they may be, mycelia are demonstrably beneficial to overall soil health and the reclamation of depleted soils for farming or re-wilding. Stamets specifically recounts the history of the world’s oldest organism, a massive mycelium in Oregon that is some 2200 years old and over 2400 acres in area. This fungus has worked on the decaying forest to create incredibly deep soil and conditions necessary for the massive trees we are familiar with in the Pacific North West. Research into the uses of fungi as tools of fixing the problems that capitalism has caused remains in its infancy, especially given the complications of encouraging mycological growth. As Tsing noted, the matsutake in particular is quite resistant to attempts at cultivation. Stamets’ and Tsing’s work shows us how novel ways of organizing ourselves and of relating in the nature we are a part of are crucial to survivance in the capitalist world. Using the work of both Tsing and Stamets we can look at how we may disrupt capitalist networks through the actions of non-human force, build new human-nature relationships that mitigate and reverse the damage, or at least clean up the damage. Beyond this however, we need to organize so that our survivance is not something just based on growing like a mushroom in the wreckage, but rather the spreading mycelium that continually makes and remakes the conditions for a better future world.

Throughout this inquiry project I have explored growing mushrooms, hunting for mushrooms, how mushrooms are connected to the history of colonization, and now what mushroom relationships let us think through and organize politically. This project has been helpful for me in one way in particular. Thinking mycologically and getting some experience harvesting and caring for mushrooms has been a goal of mine for some time, but the impetus to get to it has been lacking. I think that facilitated inquiries can be most helpful as a kick in the pants and a way to unlock the desire for learning in people that may otherwise be stagnating. I suppose we’re all kind of like mycelium in that way. Lurking underground for the right conditions to sprout forth fruiting bodies. Weird imagery.

I think the best part about this kind of experience is that it almost always precipitates a long-term process of learning, or at least some kind of skill development that you can keep with you. For me, that has been the reinvigorated commitment to thinking political relationships through a social-environmental lens, and of course the newfound skills in mushroom growing and hunting I can keep working on. Together, these provide whole new connections and conversations with a growing community of mycological appreciators that I can have, which in itself is a wonderful outcome of the project.

Thanks for a great semester team (especially to anyone who actually read any of these posts)! I hope we can keep pushing the boundaries of pedagogy together.

In solidarity,

Ry

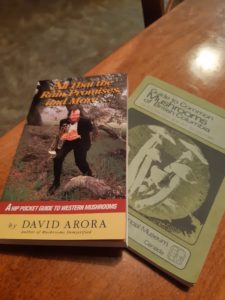

I’ve ordered a beginner mushroom growing kit from a farm up in Sayward on the north end of the Island, so that will take some time to get here. In the mean time I’m finally diving into a few books I have and calling on friends with experience to talk about wild mushrooms. My only hope is that I can live up to the style of David Arora, author of All That The Rain Promises and More. What a legend.

I’ve ordered a beginner mushroom growing kit from a farm up in Sayward on the north end of the Island, so that will take some time to get here. In the mean time I’m finally diving into a few books I have and calling on friends with experience to talk about wild mushrooms. My only hope is that I can live up to the style of David Arora, author of All That The Rain Promises and More. What a legend.